|

| The door. The actual door. |

Dedicated to wrestling with questions of faith, religion, and theology that arise in comic books and other pop culture media. Occasionally irreverent, rarely sacrilegious. Related to the podcast of the same name.

Tuesday, October 31, 2017

Happy Reformation Day (x500)!

Traditionally, October 31 is thought to be the date in 1517 that Martin Luther nailed the 95 theses to the door of All Saints' Church in Wittenberg, Germany. The church still stands, and the door is still there, although it is not easily accessed. When we visited Wittenberg a few months back as part of the "Luther 500" celebration, we were housed very near the church, now called Castle Church. And I took this picture of church history's most important door.

Monday, October 30, 2017

Podcast #014 - Scooby-Doo Team-up #13

"Rengeance!"

On this Halloweeny episode, Emily & Professor Alan talk about a nice light tale, from the delightful Scooby-Doo Team-Up title. Ghosts are disappearing all across the Earth, and the Phantom Stranger and Deadman seek out the expert ghost-finders of Mystery, Inc. to find them.

Em & the Prof also cover some great listener feedback.

Click on the player below to listen to the episode:

You may also subscribe to the podcast through iTunes or the RSS Feed.

We would love to hear from you about this issue, the podcast episode, or the podcast in general. Send e-mail feedback to dorknesstolight@gmail.com

You can follow Alan on twitter @ProfessorAlan or the podcast @DorknessToLight

On this Halloweeny episode, Emily & Professor Alan talk about a nice light tale, from the delightful Scooby-Doo Team-Up title. Ghosts are disappearing all across the Earth, and the Phantom Stranger and Deadman seek out the expert ghost-finders of Mystery, Inc. to find them.

Em & the Prof also cover some great listener feedback.

Click on the player below to listen to the episode:

You may also subscribe to the podcast through iTunes or the RSS Feed.

We would love to hear from you about this issue, the podcast episode, or the podcast in general. Send e-mail feedback to dorknesstolight@gmail.com

You can follow Alan on twitter @ProfessorAlan or the podcast @DorknessToLight

Friday, October 27, 2017

One Legacy of Luther

The following appeared in the October 27, 2017 edition of the Wall Street Journal, and was reprinted at LuxLibertas.com

How Martin Luther Advanced Freedom

By Joseph Loconte

Martin Luther was an unlikely revolutionary for human freedom. When the Augustinian monk hammered his “Ninety-Five Theses” to the Wittenberg Castle Church on Oct. 31, 1517—and unleashed the Protestant Reformation—he was still committed to the spiritual authority of the Catholic Church and retained many of the prejudices of European Christianity.

Yet Luther’s personal experience of God’s love and mercy—“I felt myself to be reborn”—supported a democratic approach to religious belief. In his theological works, Luther introduced a radical egalitarianism that helped lay the foundation for modern democracy and human rights.

Born into a German peasant family in 1483, Luther came to despise every form of spiritual elitism. He sought to replace rigid church hierarchies with “the priesthood of all believers,” the proposition that there are no qualitative differences between clergy and laity. “Just because we are all priests of equal standing,” he wrote in “An Open Letter to the Christian Nobility” (1520), “no one must push himself forward and, without the consent and choice of the rest, presume to do that which we all have equal authority.”

It was a message at odds with the vast superstructure of 16th-century Christendom. Only the monastic orders, with their vows of celibacy and poverty, could produce the spiritual athletes of the church, the thinking went. But to Luther the monasteries were hotbeds of avarice and pride. He wanted them abolished, writing in “The Babylonian Captivity of the Church” (1520) that “pretentious lives, lived under vows are more hostile to faith than anything else can be.”

Luther applied the same logic to the doctrine of Christian vocation. Resisting the stark divisions between “secular” and “religious” occupations, he dignified all legitimate work. “A shoemaker, a smith, a farmer, each has his manual occupation and work; and, yet, at the same time, all are eligible to act as priests and bishops,” he wrote.

An oil on panel portrait of Martin Luther, circa 1526.

Luther took an ax to the legal culture that shielded priests and bishops from criminal prosecution simply because they held church offices. “It is intolerable that in canon law, the freedom, person, and goods of the clergy should be given this exemption, as if the laymen were not exactly as spiritual, and as good Christians, as they, or did not equally belong to the church.” Here was a religious basis for the principle of equal justice under the law, a core tenet of liberal democracy.

Perhaps Luther’s most subversive act was his translation of the New Testament into German, a feat scholars estimate he accomplished in three months. The papacy had controlled the interpretation of Scripture, available almost exclusively in Latin, the language of the clergy and the highly educated. But Luther wanted the Bible translated and read as widely as possible: “We must inquire about this of the mother in the home, the children on the street, the common man in the marketplace,” he explained in “On Translation: An Open Letter” (1530). “We must be guided by their language, the way they speak, and do our translating accordingly.”

Luther always elevated the individual believer, armed with the Bible, above any earthly authority. This was the heart of his defiance at the Diet of Worms: “My conscience is captive to the Word of God. I cannot and I will not recant anything, for to go against conscience is neither right nor safe. Here I stand.” Neither prince nor pope could invade the sanctuary of his conscience. This, he proclaimed, is the “inestimable power and liberty” belonging to every Christian.

It would be hard to imagine a more radical break with centuries of church teaching and tradition. Luther’s intense study of the Bible—part of his anguished quest to be reconciled to God—made these great innovations possible. Convinced that the teachings of Christ had become twisted into an “unbearable bondage of human works and laws,” he preached a gospel of freedom. Salvation, he taught, was a gift from God available to everyone through faith in Jesus and his sacrificial death.

In 1520, some three years after publishing his theses, Luther released “On the Freedom of a Christian,” his manifesto on the privileges and obligations of every believer. It became a publishing phenomenon. “A Christian has no need of any work or law in order to be saved,” he insisted, “since through faith he is free from every law and does everything out of pure liberty and freely.” Christian liberty of this kind provided no excuse for libertinism. Just the opposite: “I will therefore give myself as a Christ to my neighbor, just as Christ offered himself to me.”

Luther offered more than a theory of individual empowerment. He delivered a spiritual bill of rights. Generations of reformers—from John Locke to Martin Luther King Jr.—would praise his achievement. Half a millennium later, his message of freedom has not lost its power.

Saturday, October 14, 2017

Dan Brown Does it Again :O(

A researcher who was turned into a character in Dan Brown's latest novel "Origin," rebuts how he is portrayed in the book, and how Brown characterizes what his research implies.

From the Wall Street Journal, 10/13/2017, reprinted at LuxLibertas.com.

I recently learned that I play a role in Dan Brown’s new novel,

“Origin.” Mr. Brown writes that Jeremy England, an MIT physics

professor, “was currently the toast of Boston academia, having caused a

global stir” with his work on biophysics. The description is flattering,

but Mr. Brown errs when he gets to the meaning of my research. One of

his characters explains that my literary doppelgänger may have

“identified the underlying physical principle driving the origin and

evolution of life.” If the fictional Jeremy England’s theory is right,

the suggestion goes, it would be an earth-shattering disproof of every

other story of creation. All religions might even become obsolete.

It would be easy to criticize my fictional self’s theories based on Mr. Brown’s brief description, but it would also be unfair. My actual research on how lifelike behaviors emerge in inanimate matter is widely available, whereas the Dan Brown character’s work is only vaguely described. There’s no real science in the book to argue over.

My true concern is with my double’s attitude in the book. He is a prop for a billionaire futurist whose mission is to demonstrate that science has made God irrelevant. In that role, Jeremy England says he is just “trying to describe the way things ‘are’ in the universe” and that he “will leave the spiritual implications to the clerics and philosophers.”

Two years ago I wrote in Commentary magazine that it is impossible simply to describe “the way things are” without first making the significant choice of what language to speak in. The language of physics can be extremely useful in talking about the world, but it can never address everything that needs to be said about human life. Equations can elegantly explain how an airplane stays in the air, but they cannot convey the awe someone feels when flying above the clouds. I’m disappointed in my fictional self for being so blithely uninterested in what lies beyond the narrow confines of his technical field.

I’m a scientist, but I also study and live by the Hebrew Bible. To me, the idea that physics could prove that the God of Abraham is not the creator and ruler of the world reflects a serious misunderstanding—of both the scientific method and the function of the biblical text.

Science is an approach to common experience. It addresses what is objectively measurable by inventing models that summarize the world’s partial predictability. In contrast, the biblical God tells Moses at the burning bush: “I will be what I will be.” He is addressing the uncertainty the future brings for all. No prediction can ever fully answer the question of what will happen next.

Humans will always face a choice about how to react to the unknowable future. Encounters between God and the Hebrew prophets are often described in terms of covenants, partly to emphasize that seeing the hand of God at work starts with a conscious decision to view the world a certain way.

Consider someone who assumes that all existence is the work of a creator who speaks through the events of the world. He can follow that assumption down the road and decide whether God seems to be keeping his side of the bargain. Many of us live like this and feel that with time our trust in him has been affirmed. There’s no scientific argument for this way of drawing meaning from experience. But there’s no way science could disprove it either, because it is outside the scope of scientific inquiry.

Some religious adherents do make claims that deserve to be disputed by science. For instance, they may openly acknowledge that their deepest beliefs are incompatible with the existence of dinosaurs. The fictional me—and perhaps Mr. Brown too—might hope to put these holdouts back on their heels. But disputes like this never answer the most important question: Do we need to keep learning about God? For my part, in light of everything I know, I am certain that we do.

Mr. England is a professor of physics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

From the Wall Street Journal, 10/13/2017, reprinted at LuxLibertas.com.

Dan Brown Can’t Cite Me to Disprove God

By Jeremy England

It would be easy to criticize my fictional self’s theories based on Mr. Brown’s brief description, but it would also be unfair. My actual research on how lifelike behaviors emerge in inanimate matter is widely available, whereas the Dan Brown character’s work is only vaguely described. There’s no real science in the book to argue over.

My true concern is with my double’s attitude in the book. He is a prop for a billionaire futurist whose mission is to demonstrate that science has made God irrelevant. In that role, Jeremy England says he is just “trying to describe the way things ‘are’ in the universe” and that he “will leave the spiritual implications to the clerics and philosophers.”

Two years ago I wrote in Commentary magazine that it is impossible simply to describe “the way things are” without first making the significant choice of what language to speak in. The language of physics can be extremely useful in talking about the world, but it can never address everything that needs to be said about human life. Equations can elegantly explain how an airplane stays in the air, but they cannot convey the awe someone feels when flying above the clouds. I’m disappointed in my fictional self for being so blithely uninterested in what lies beyond the narrow confines of his technical field.

I’m a scientist, but I also study and live by the Hebrew Bible. To me, the idea that physics could prove that the God of Abraham is not the creator and ruler of the world reflects a serious misunderstanding—of both the scientific method and the function of the biblical text.

Science is an approach to common experience. It addresses what is objectively measurable by inventing models that summarize the world’s partial predictability. In contrast, the biblical God tells Moses at the burning bush: “I will be what I will be.” He is addressing the uncertainty the future brings for all. No prediction can ever fully answer the question of what will happen next.

Humans will always face a choice about how to react to the unknowable future. Encounters between God and the Hebrew prophets are often described in terms of covenants, partly to emphasize that seeing the hand of God at work starts with a conscious decision to view the world a certain way.

Consider someone who assumes that all existence is the work of a creator who speaks through the events of the world. He can follow that assumption down the road and decide whether God seems to be keeping his side of the bargain. Many of us live like this and feel that with time our trust in him has been affirmed. There’s no scientific argument for this way of drawing meaning from experience. But there’s no way science could disprove it either, because it is outside the scope of scientific inquiry.

Some religious adherents do make claims that deserve to be disputed by science. For instance, they may openly acknowledge that their deepest beliefs are incompatible with the existence of dinosaurs. The fictional me—and perhaps Mr. Brown too—might hope to put these holdouts back on their heels. But disputes like this never answer the most important question: Do we need to keep learning about God? For my part, in light of everything I know, I am certain that we do.

Mr. England is a professor of physics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Sunday, October 8, 2017

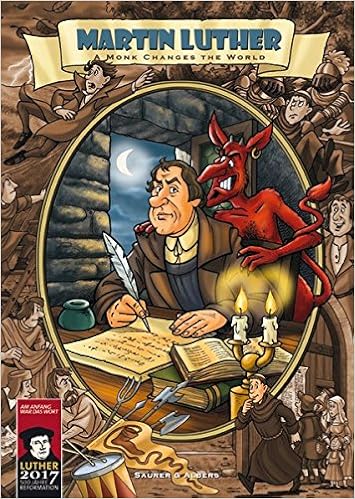

Comic Book Review: Martin Luther

Martin Luther: A Monk Changes the World, by Johannes Saurer & Ulrike Albers. Translated by Christine Gollmart.

Martin Luther: A Monk Changes the World, by Johannes Saurer & Ulrike Albers. Translated by Christine Gollmart.Martin Luther lived a very action-packed life, and condensing it into 26 comic book pages is a very difficult task. But this short graphic novel manages to hit all of the high points, and tell the story with the drama that it deserves.

The book rarely stays in one location for more than a few pages, and manages to play scenes in Eisleben, Mansfeld, Erfurt, Augsburg, Worms, Wartburg Castle, Schmalkalden, Torgau, and (of course) Wittenberg.

The book also manages to include as characters a number of Luther's allies, including Justus Jonas, Philipp Melanchthon, and his wife, the wonderful Katharina von Bora.

This is an informative and interesting biography. And considering the pace the story has to move at to cover the highlights, it is also quite entertaining.

The graphic novel may be purchased here, from Amazon.

Source: We picked this graphic novel up at a small store in Wittenberg, when we visited Germany during the Luther 500 celebration, which he talked about on a podcast episode here.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)